First spun samples!

I can’t believe we’re already at update #3 of my experiment! A lot of work goes into the set up phase of an experiment, and isn’t really seen much, which is why I wrote a blog post about it for the EXARC website. Visualising the specific steps can be difficult when you’re just starting out, so hopefully my post helps newer experimenters get under way with exploring their ideas.

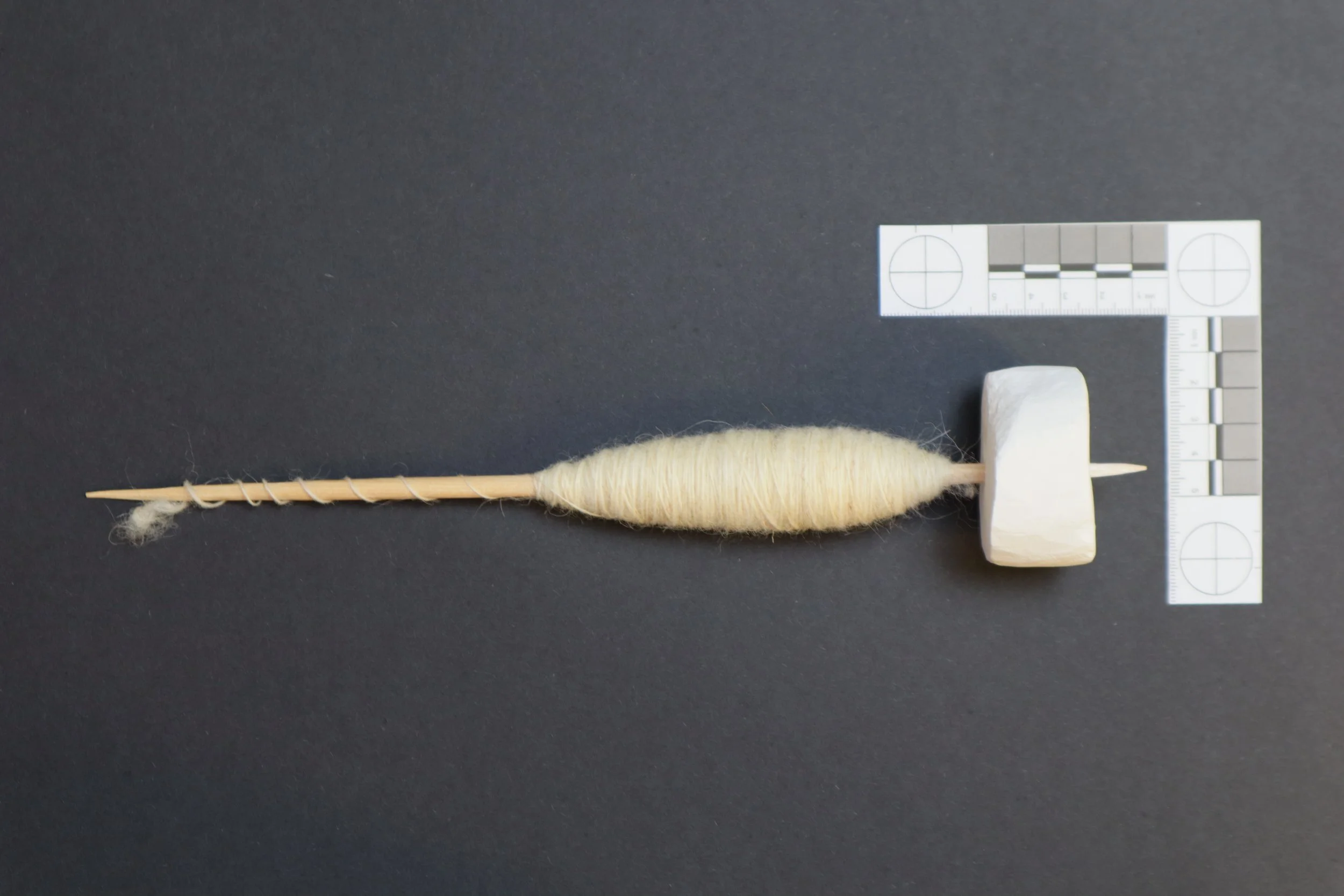

Bergschaf wool and chalk whorl carved to resemble an example from Danebury hillfort.

In this update, I am happy to share that I’ve spun my first sample! I was following a couple of experiments that had been conducted previously (see the bibliography at the end) and one of them listed the specific wool used, bergschaf. I was not familiar with this wool, but it was selected because it was easy to source for the large volume of experiments that were to be conducted (Kania 2015). The earlier experiment, by Gromer (2005), listed no specific breed. In experimental archaeology (and archaeology in general, but even more so for experiments), it’s really important to build upon previous work because there are always a ton of different variables to consider. Therefore, I am using bergschaf for this first round of my spinning experiment (which will yield 12 samples).

I will repeat this part of the experiment again twice more, with two different wools, so I will have 36 samples. And this is only the beginning.

Comprehensive approaches are always very time consuming but they yield the most insightful data, which is my primary goal. Spindling experiments are fairly rare in textile studies, and they usually are exploratory in nature. My experiments will provide researchers with a reference collection of wools, methods, and whorl ranges that can shed light on textile production in a vast range of cultures around the world.

This first sample aimed to spin a yarn as thinly as was comfortable with the bergschaf wool, using a supported style of spinning. After a test spin with some wool I had handy, I found that it was relatively easy to spin with. I hardly even noticed that my hand carved (from dowels) spindle stick was a bit rough on the surface—it quickly became smooth with the wool twisting over the tip. The wobble in the whorl barely registered in my consciousness as I built up the cop of fresh yarn. My biggest hurdle was getting used to the bergschaf wool, which didn’t behave quite like I expected (I’ll talk about that later).

Removing biases from experiments is tough, especially if you’re the one doing all the spinning. To minimise this, I have decided to wait until I have spun all the samples for a single category, then analyse them. Hopefully, this will yield really good results. So, I’ll have to give you an update about my results so far in a much later update. Until then, I’ll post some photos and videos of my work so far.

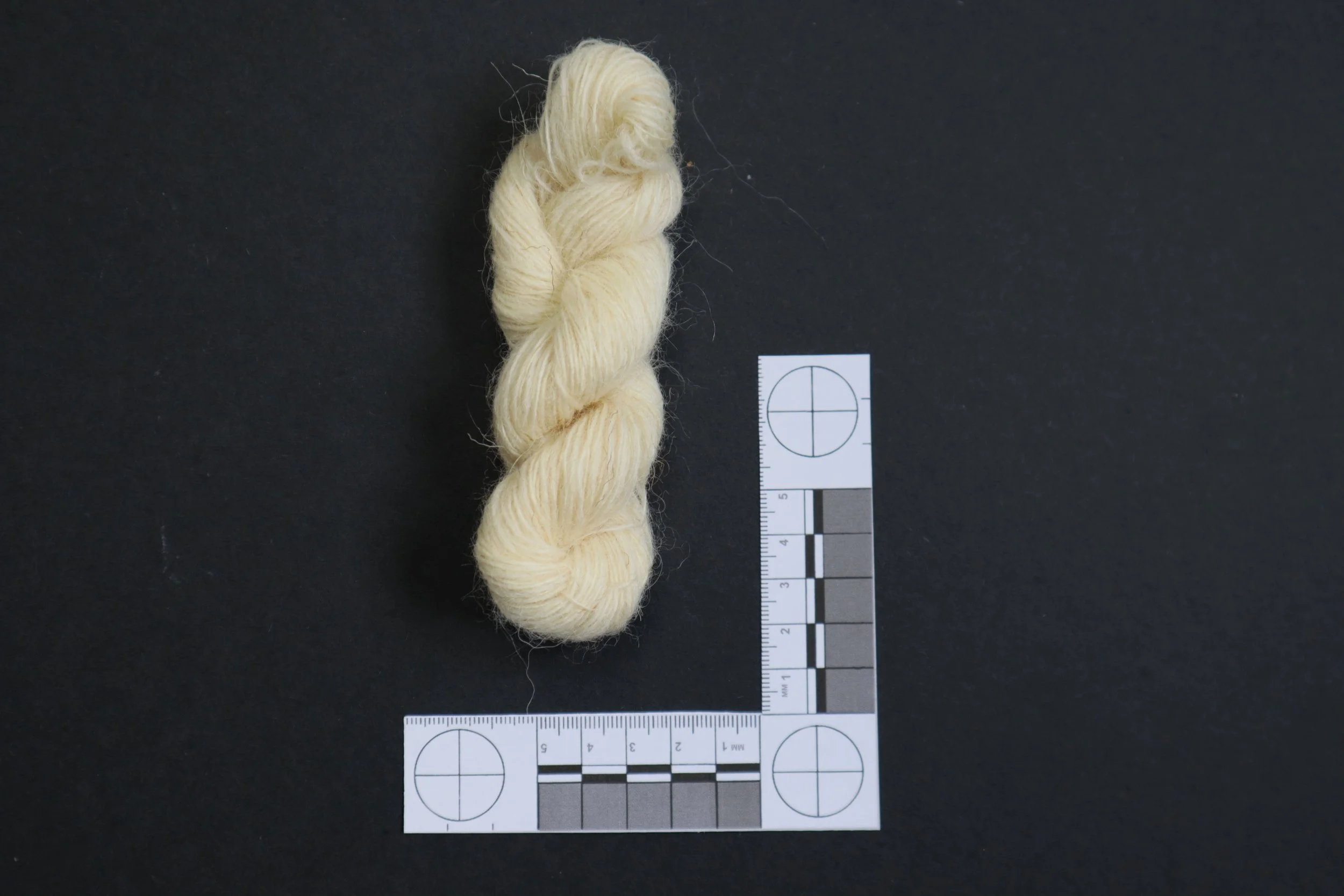

One of the sample skeins produced as part of this project.

Grömer, K. (2005) ‘Efficiency and technique—Experiments with original spindle whorls’, in Bichler, P., Grömer, K., Hofmann-de Keijzer, R., Kern, A., and Reschreiter, H. (eds.) Hallstatt Textiles: Technical analysis, scientific investigation, and experiment on Iron Age textiles. BAR International Series 1351. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Kania, K. (2015) ‘Soft yarns, hard facts? Evaluating the results of a large-scale hand-spinning experiment’, Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 7(1), pp.113-130.